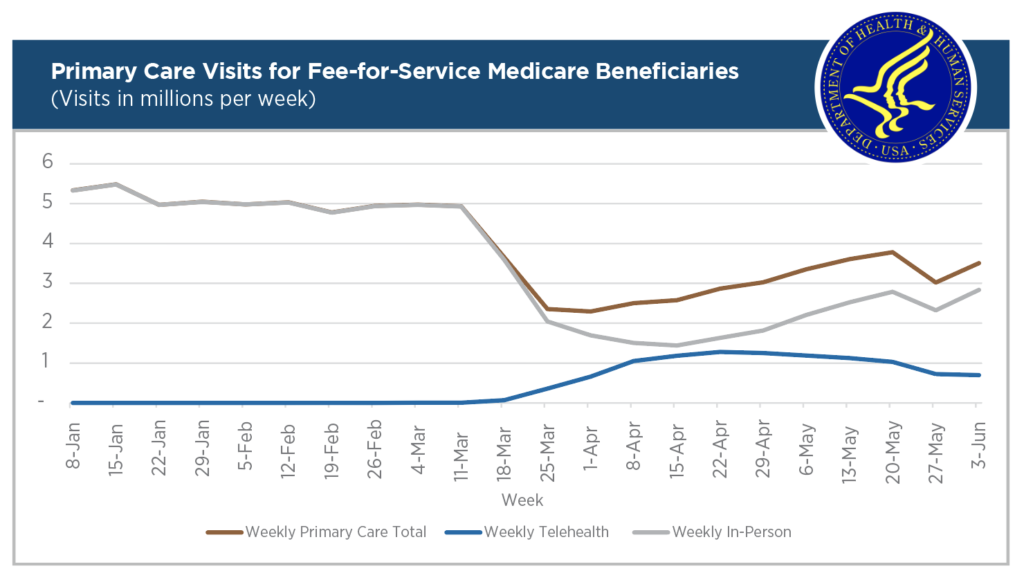

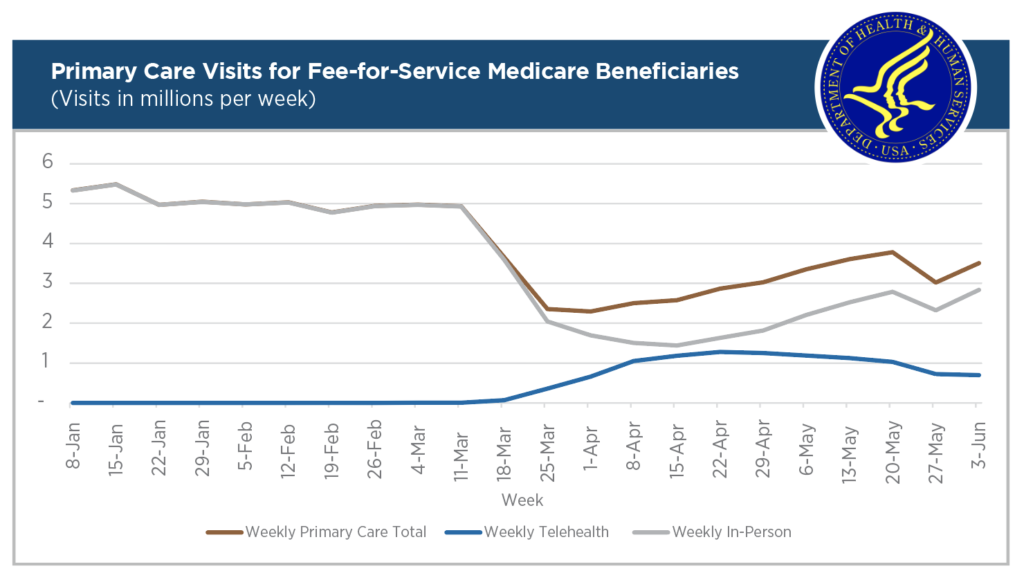

The Coronavirus pandemic has accelerated adoption of telemedicine and telehealth in patient populations across the U.S. and worldwide. Overall consumer use of telehealth visits has soared from 11% last year to 46% in 2020, according to a May McKinsey & Company report. On the federal side, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) reported virtual visits for Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) beneficiaries surged from approximately 14,000 in February 2020 to almost 1.7 million in the last week of April. That corresponds to almost 45% of Medicare primary care visits being provided through telehealth in April, versus 0.1% in February. Veterans, too, have been cared for by practitioners utilizing 120,000 telehealth appointments per week as of May, up from 10,000 per week before the pandemic hit. Private payer telehealth use has also skyrocketed. Nearly $4 billion for telehealth visits was billed in March and April of 2020, compared to $60 million for the same period in 2019, according to data collected by FAIR Health.

Source: HHS Issue Brief on Medicare Beneficiary Use of Telehealth Visits, July 28th.

The spike in telehealth use has multiple facets—an extended, contagious pandemic causing closures and stay-at-home orders; increased treatment needs for those infected by COVID-19, as well as those who missed appointments or needed acute care for other reasons; the availability of technology and equipment; and significant changes in laws and policies, both federal and state, that eased or eliminated telehealth restrictions.

Definitions of telemedicine and telehealth differ across sectors and jurisdictions and within federal departments. While there is no universal definition of telehealth, there are commonly used terms. Telemedicine, or remote clinical services, is the core, and could be thought of as the center of telehealth. Telehealth is the larger envelope around, and including, telemedicine. It is the “use of electronic information and telecommunications technologies to support long-distance clinical health care, patient and professional health-related education, public health, and health administration,” as defined by the Health Resources Services Administration (HRSA) at HHS. The Congressional Research Service offers that telehealth modalities include: (1) clinical video telehealth or live video, (2) mobile health, (3) remote patient monitoring, and (4) store-and-forward technology, as well as telephones and fax machines.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) defines telemedicine as “… using telecommunications technologies to support the delivery of all kinds of medical, diagnostic, and treatment-related services, usually by doctors,” and telehealth as “a wider variety of remote health care services beyond the doctor-patient relationship.”

For the federal Medicare program, which covers more Americans than any other payer, CMS uses definitions determined by statute and regulation. Further, each state defines and addresses telehealth uniquely for its own reimbursement and licensing requirements and administration of Medicaid programs. Due to COVID-19, states and the federal government have—temporarily or permanently—changed many policies supportive of telehealth through legislation and administrative changes. The landscape will keep changing—a flood of new legislation related to telehealth has extended across the country and in Washington, D.C.

The Congressional response to the coronavirus pandemic fueled Medicare telehealth growth. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the CARES Act altered telehealth requirements and removed restrictions for Medicare telehealth coverage. Before the CARES Act, Medicare patients generally could not receive telemedicine services in their homes. For the duration of the Public Health Emergency, they can. Video visits had been restricted geographically to patients in rural areas and to those participating in limited demonstration projects; practitioners were required to be in certain locations as well. Only certain practitioners and types of appointments could be considered for telehealth usage. Those restrictions have been lifted.

On the technical side, Medicare required an interactive two-way telecommunications system (real-time audio and video). This was expanded to allow for asynchronous and audio-only communication. The platform requirements due to Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) privacy and security needs were temporarily eased to include FaceTime, Zoom, Skype and others. Further, types of allowed visits were expanded, and eligible practitioners now include physical therapists, occupational therapists, and speech language pathologists. Federal cross-state licensure requirements were relaxed; however, state requirements still apply. The CARES Act and resulting CMS administrative changes opened telehealth to all Medicare recipients to receive more varied types of care in their homes by practitioners who may also be in their homes in a different state. The Center for Connected Health Policy (CCHP), the federally-designated source for telehealth policy, has summarized the changes.

Many states took action to broaden use of telehealth, requesting and receiving waivers from CMS. In addition, states initiated their own policy and legal changes, both on a temporary and permanent basis, to support use of telehealth modalities. Forty-seven states have pending or enacted telehealth legislation or undertook administrative action related to telehealth. An inventory of state actions taken by Governors, Medicaid Programs, and medical or other regulatory state boards is available from the CCHP.

Will Telehealth Growth Continue?

McKinsey & Company’s May 2020 report on telehealth forecasts that “up to $250 billion of current U.S. healthcare spend could potentially be virtualized” if telehealth continues to be expanded beyond virtual urgent care into office visits, home health services, and diverting emergency department visits. Seema Varma, CMS Administrator, is supportive of continued telehealth expansion, with a focus on health outcomes. She stated that “reversing course [on telehealth] would be a mistake.”

On August 3rd, President Trump issued an Executive Order (E.O. 13941) “to increase access to, improve the quality of, and improve the financial economics of rural healthcare, including by increasing access to high-quality care through telehealth.” The President noted the high usage of telehealth by Medicare recipients during the coronavirus surge and the specific needs of rural communities. As part of the E.O., President Trump required a proposal on payment mechanisms and “a strategy to improve rural health by improving the physical and communications healthcare infrastructure available to rural Americans.”

We’ve been providing telehealth services at a rate and a speed during this pandemic, and the President wants to make that benefit permanent for Medicare recipients.

CMS Administrator Varma, August 3rd

The Executive Order does not make the telehealth benefits permanent. Removing geographic and originating site restrictions from Medicare coverage, or giving the HHS Secretary the authority to permanently expand the types of telehealth services covered by Medicare, require changes in law.

Bills in Congress

Over 20 bills have been introduced in the House and at least a dozen in the Senate to address telehealth access post-COVID, including bills that emphasize rural areas, veterans, and Tribal organizations. The focus of several bills, such as Rep. Sherrill’s (D-NJ) Protect Telehealth Access Act of 2020 (H.R. 7391) and Sen. Alexander’s (R-TN) Telehealth Modernization Act (S. 4375), is making the current COVID-related telehealth expansion for the Medicare population permanent. There is also interest in additional funding for the FCC’s COVID-19 Telehealth Program.

When, or if, the House and Senate reach agreement on additional COVID-19 relief funding, they may also address permanent status for some of the existing emergency federal telehealth waivers. Because telehealth requirements increase demand for connectivity for both rural and urban patient populations, we expect future infrastructure and funding initiatives to boost connectivity and invest in telehealth-supporting information technology.

The COVID crisis prioritizes access to care and continuity of care and catapults telehealth into prominent use. The next challenges for telehealth technology are full integration into patient care, exceeding expectations of providers and patients, ease of use of technology and its security, measuring outcomes, and overcoming technology barriers in the rural and urban underserved patient populations.