August was an expensive month. Last month, President Biden signed three laws and took administrative actions with an estimated price tag of $800 billion to $1.6 trillion over 10 years. During that same month, the Chairman of the Fed reiterated his commitment to tackle inflation in blunt terms and the 10-year Treasury rate rose above 3%, double its level at the start of the year. While the latest federal budget data show the deficit declining from the extraordinary levels of the two previous years as a result of the roll-off of emergency and stimulus spending and a larger-than-expected surge in revenues, the federal debt service bill is growing rapidly, exceeding last year’s level by $121 billion (+32%) through the first 11 months of the fiscal year.

Inflation and the economy are the public’s chief worry and the President highlighted his actions to combat inflation at a September 13th White House ceremony heralding the Inflation Reduction Act. The same day, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported inflation remained at stubbornly high levels (+8.3% on annual basis).

Despite the grim inflation news, the U.S. economy is showing remarkable resiliency with the unemployment rate at historically low levels (3.7%). The Biden administration acknowledges the inflation problem, but points to the recent steep decline in gasoline prices from their peaks earlier this summer and argues that the Inflation Reduction Act and their other actions will bring inflation down.

Our plan has worked. Due to the American Rescue Plan and our vaccination campaign, the United States experienced the fastest pace of job creation in our history. Household balance sheets are strong. Businesses continue to invest. Our broad and inclusive recovery has outpaced that of many other large economies.

Treasury Secretary Yellen,

September 8

While there is a growing acknowledgment that Washington overdid it with both fiscal and monetary stimulus and the Fed is now actively tightening monetary policy, that is not the case with fiscal policy. Washington continues deficit spending, frequently on a bipartisan basis.

To assess the current fiscal outlook, we review the Congressional Budget Office’s May 2022 deficit forecast, the additional cost of major legislation enacted and other actions taken this year and the potential costs of rising interest rates.

THE GROWING PRICE TAG: LEGISLATION, ADMINISTRATIVE ACTIONS & FINANCING COSTS

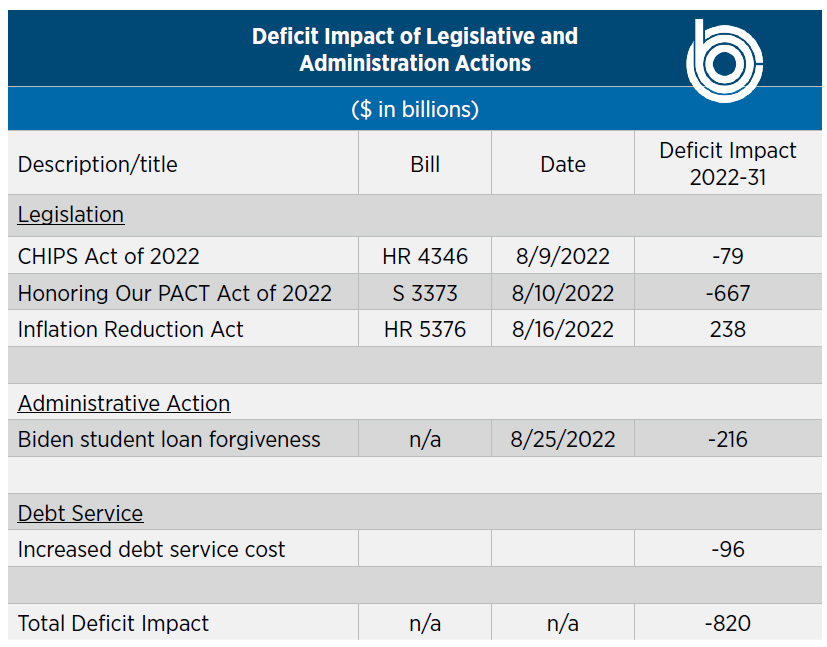

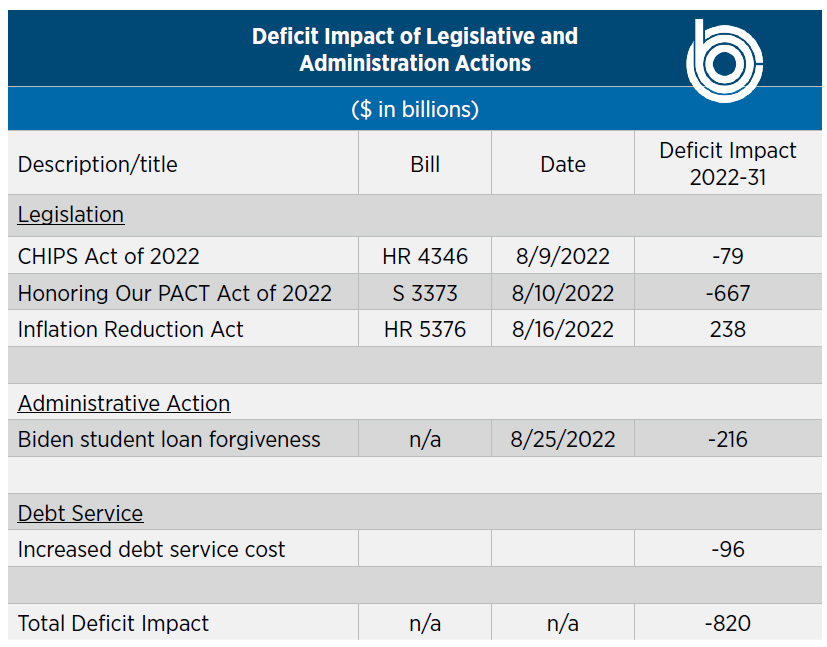

In August, President Biden signed three laws and took an administrative action, all with significant long-term costs: the bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act of 2022, the bipartisan Honoring our PACT Act of 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act (which passed with no Republican support), and unilateral action to expand student loan subsidies and forgive loans.

Chart I summarizes the CBO 10-year estimate for each of those laws. We do not yet have a CBO or OMB estimate of the cost of the President’s student loan forgiveness actions. The Penn Wharton Budget Model put a price tag of between $429 billion and $1 trillion over 10 years on the President’s action. Unlike most other Federal spending, the student loan program and other federal credit programs are budgeted on an accrual instead of a cash basis. To dampen concerns about the cost of the President’s action, the White House estimated its impact on federal cash flows but not the full accrual cost. For discussion purposes the White House estimates are included in the chart, actual costs should exceed these estimates.

Chart I Sources: Congressional Budget Office and the White House

THE RISKS AND COSTS OF HIGHER INTEREST RATES

There has been an explosion of federal debt with the 2008-9 financial crisis and then the pandemic. That huge surge of debt was accompanied by extraordinary actions by the Fed to essentially keep interest rates at zero. FY20 best illustrates the benefits of Fed’s actions to the Treasury. In that year, while the debt increased by 20%, low interest rates reduced debt service costs by 8.6%.

The Fed was clearly behind the curve in tackling inflation and did not begin to raise interest rates until March, about the same time CBO locked in the economic forecast underlying its latest deficit projections. CBO’s May forecast almost certainly under-estimates inflation and interest rates for this year and FY23. We also expect interest rates to exceed CBO’s 10-year estimates. For the interest rate on the 10-year Treasury note, one of the benchmarks of its forecast, CBO assumed it would average 2.4% this calendar year. The 10-year rate surpassed the 2.4% mark in April and rose above 3.5% on September 19th (the increase in interest rates on shorter term Treasury securities has been even more dramatic). Even with the modest rise in interest rates that underlie CBO’s current deficit projections, their projections show the cost of financing the federal debt doubling by 2027 and exceeding national defense expenditures in 2030.

CBO has a workbook that allows one to model how changes in economic assumptions would affect their budget deficit projections. Based on CBO’s model, if the 10-year Treasury rate was a full 1% higher than its May projection for one year and then returned to its baseline projections, that would result in an $81 billion increase in the deficit for the current year and $357 billion increase in the deficit over 10 years. If interest rates were a full 1% above CBO’s projections for 10 years, that would result in a $2.5 trillion increase in the deficit over that time period. When baseline estimates are updated in February, we expect the risk closer to the high end of that range.

To date, the higher cost of interest rates to service the debt has been offset by stronger than projected growth in federal revenues. With the economy already slowing, the Fed increasing interest rates by another 75 basis points on September 21, 2022 and signaling more rate hikes are coming, the risk of a recession rises along with higher deficits due to lower revenues and higher income support spending. That in turn will result in a growing share of the Federal budget being used to simply pay for the cost of a rising debt and will likely lead to Congress slowing the spending growth rate approved over the past six years.

The prospect for divided government limits prospects for a long-term spending or deficit reduction deal. It may also end the federal government’s unprecedented 3-year deficit spending spree.