January 28, 2021

Biden Agenda Faces Closely-Divided Congress

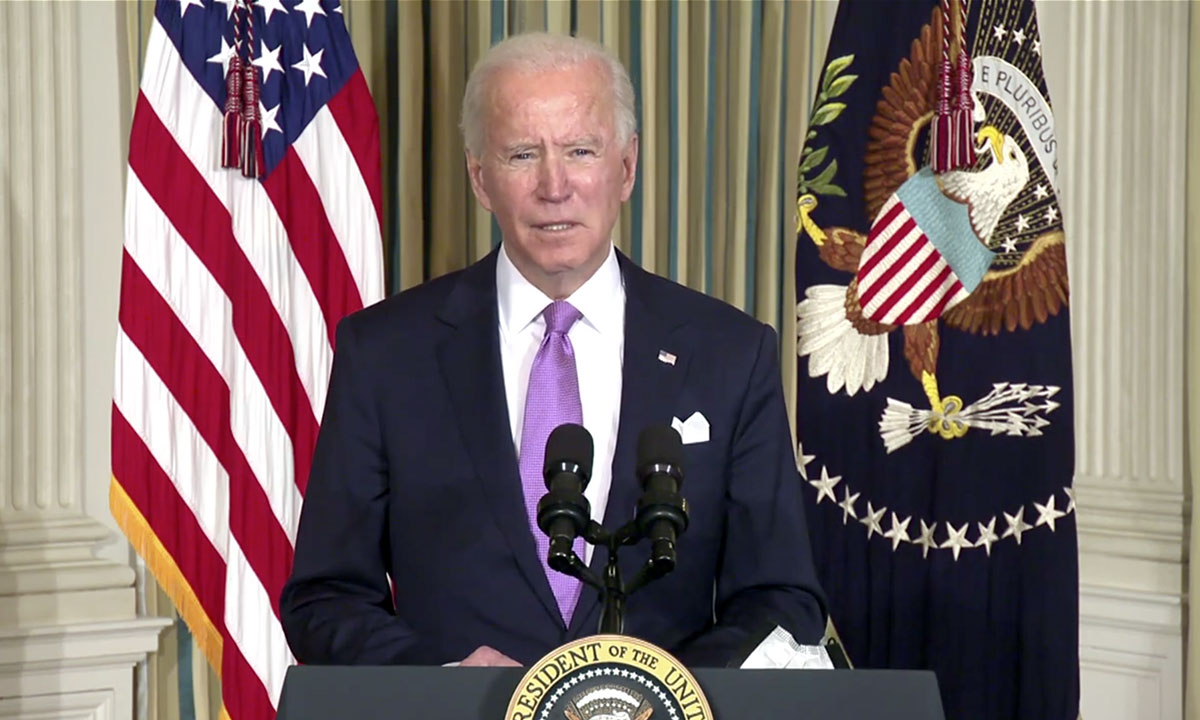

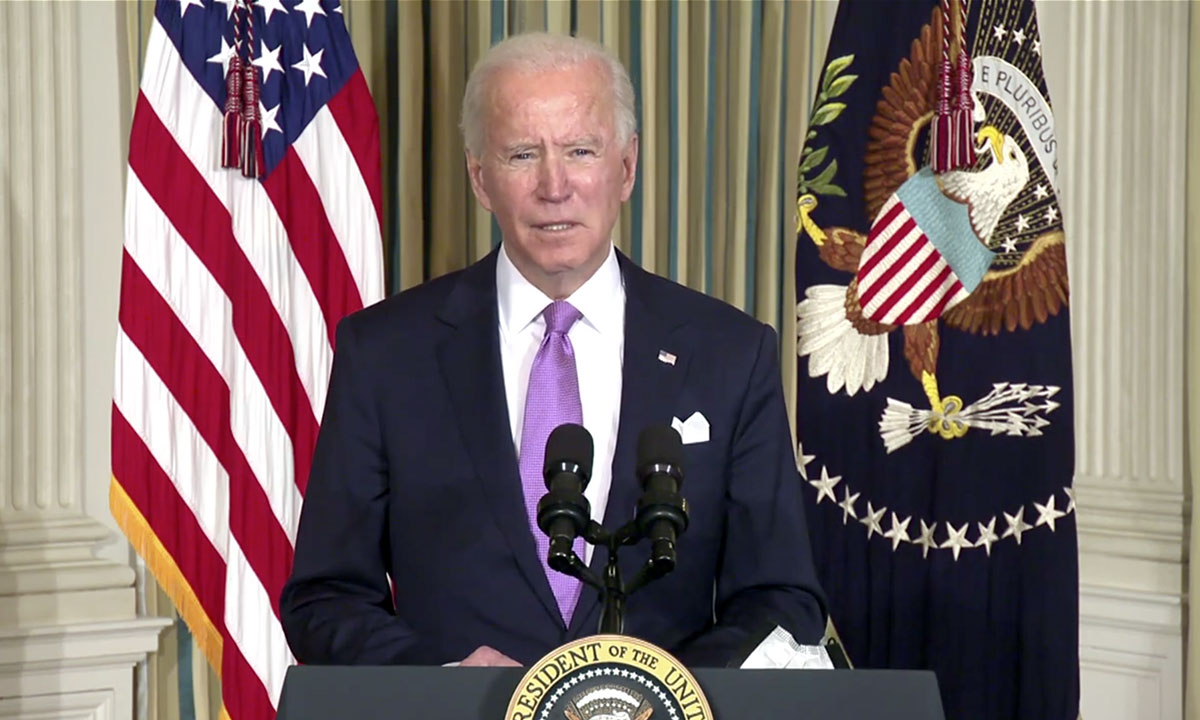

Looking at the congressional agenda for this year, we can break it into the following categories: 1) nominations; 2) impeachment; 3) the next COVID package; 4) the budget; and 5) other legislation. Biden’s agenda and priorities will drive legislation, but hurdles and obstacles along the way will impact implementation.

Meet Me in the Middle?

The Senate frequently is the chokepoint for legislation. The Senate has sole responsibility for nominations and Trump’s impeachment trial, which will add to the potential traffic jam. A Senate majority leader’s most precious commodity is floor time. The leader needs to move priorities and must-do legislation but avoid getting trapped in cul-de-sacs. If a majority leader is not careful, a protracted debate can consume floor time that could be better spent on other legislation. He or she must weigh using Senate rules and reaching across the aisle to get things done.

For the 117th Congress, the Senate still needs to organize. The Senate has had a 50-50 split only one other time — after the 2000 election with Vice President Cheney’s tie-breaking vote giving Republicans control of the Senate. Unlike 2000, Senate election results were not finalized until after Georgia’s January 5th special elections.

In 2021, Vice President Harris will break ties and give her party the Senate majority. In 2001, Senate leaders Lott (R-MS) and Daschle (D-SD) developed a power-sharing arrangement that they began to work on soon after the election. That power-sharing agreement was adopted on January 5, 2001 and remained in effect until June 5, 2001, when Senator Jeffords (R-VT) switched political parties, giving the Democrats a 51-49 majority.

Summary of the Senate 2001 Power-Sharing Agreement |

|

The Senate’s 2001 power-sharing agreement did not completely preclude consideration of partisan legislation and did not apply to conference reports. When President Bush proposed legislation to reduce taxes, Congress used the expedited budget reconciliation process. Lott bypassed the committees and took the House-passed reconciliation bill to the floor, passed it, and appointed a majority of Republicans to the conference committee. That reconciliation bill cleared the Senate and became law before Jeffords switched parties.

For the 117th Congress, the two Senate leaders are finalizing a Senate power-sharing agreement after overcoming a sticking point on maintaining the legislative filibuster.

While the Senate is a chokepoint, getting partisan legislation through the House is no given. With the current membership of the House, Speaker Pelosi (D-CA) can only afford to lose five votes. Two unfilled seats could go to Republicans, shrinking that margin. And, Biden has nominated four sitting Democrats to administration posts. While all are safe seats for Democrats, temporary vacancies shrink Pelosi’s majority.

House Majority Whip Clyburn (D-SC), who was instrumental in Biden securing the Democratic nomination, noted Biden’s challenge: “We’ve got a caucus that’s blue dogs, yellow dogs, moderates, conservatives, liberals. We’ve got them all. He may have a harder job keeping us united than getting bipartisanship going.” If Biden fails to get bipartisan cooperation, Clyburn has urged him to use his executive authority.

The nation is facing unprecedented challenges: the greatest economic crisis in seventy-five years, the greatest public health crisis in a century, the climate crisis, and worsening income inequality and racial injustice. The Senate Democratic Majority, working with President-elect Biden and our House Democratic colleagues, is committed to delivering the bold change our country demands, and the help that our people need.

Senate Democratic Leader Schumer, (D-NY), January 12th

What Comes Next

For a host of reasons, it is challenging to predict how the year will unfold, but we expect the usual steps in the budget and legislative process to be delayed. The following are some items the Congress will address.

CBO Budget and Economic Outlook. Usually released in late January, this will probably be delayed into February. This report is critical for congressional budget decisions since it provides a budget and economic forecast and includes the baseline that governs cost estimates for legislation.

Biden Nominations. Usually, the Senate expedites confirmation for key positions and less controversial nominees for a new President. President George W. Bush had a 50-50 Senate and nominations could be filibustered, but even with those obstacles, seven cabinet members were confirmed on his first day in office. With a Republican Senate and new rules that prevented a filibuster of nominations, Trump only had two cabinet members confirmed on his first day. Biden had one. That does not mean Biden is going to face the same obstacles, but it suggests that Republicans can slow the process as Democrats did in 2017.

Impeachment. The House submitted the articles of impeachment to the Senate on January 25th. The Senate is now required to conduct a trial. This could heighten partisanship, consume valuable floor time, and divert the Senate’s attention from Biden’s agenda.

Next COVID Bill. The content and timing of the next package will depend on bipartisan negotiations, the course of the virus, vaccine rollout, and economic factors. A key action-forcing deadline is March 14th when unemployment insurance extensions and expansions included in the December COVID package expire. Other provisions lapse later in March, April, and June.

President’s Budget. It is impossible for any new President to meet the deadline for submission of the President’s budget (February 1st this year). Since the budget deadline was changed in 1990, subsequent new Presidents have submitted a budget framework in late February followed by the full budget submission in April or May. It is unclear how Biden will proceed, but past practice suggests that release of the framework will be delayed to March with the full budget submission as late as May.