October 05, 2020

Washington Gridlock Forces Tough Choices for State and Local Governments

A record-setting decade-long trend of state revenue growth ended suddenly in March as the COVID-19 global pandemic caused a swift and devastating economic crisis. Governors, mayors, and state and local organizations have been sounding alarms about the effect of pandemic-caused revenue loss on the budgets of states and localities. Closures and stay-at-home orders negatively impacted revenue from sales tax, personal income and corporate taxes, fees, tolls, and consumption and gambling taxes. Property tax revenues, while less sensitive, are also expected to decline. An Urban Institute analysis concludes that state tax revenues turned “sharply negative” with a 5.9% decline between July 2019 and June 2020 (the full fiscal year for 46 states). During that time, personal income taxes declined 10.5%, corporate income taxes declined 16.3%, and sales taxes increased 0.2%, according to the study.

Because of the time lag between changes in economic activity and the changes in key revenue sources like income and property taxes, these statistics understate the full impact of the challenges facing state and local government. Most states entered FY21 with rosy financials for the first three-quarters of FY20. That cushioned the short-term financial impact of COVID-19 in their 4th quarter. There is no cushion in FY21. According to a September Pew report on state fiscal health: “Projections for fiscal 2021 are more dire, with many states anticipating double-digit drops in general fund revenue from pre-pandemic projections.” The National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO) predicts that state revenue losses will exceed the 11.6% drop states experienced during and after the Great Recession, with the revenue loss in several states exceeding 20%.

From the county and municipality perspective, state funding comprises 20-25% of their revenue. The remainder, a mix of taxes and fees for services and utilities, is primarily derived from economic activity within the communities, so as the community suffers economically the revenue base follows suit. Counties and cities have concerns over the reliability of the state funding stream as states struggle financially. The National Association of Counties (NACO) reports that 38 states have notified their counties that aid to localities and counties is being cut or is at risk. New York’s enacted FY21 budget included $8 billion in cuts to state aid to counties and localities.

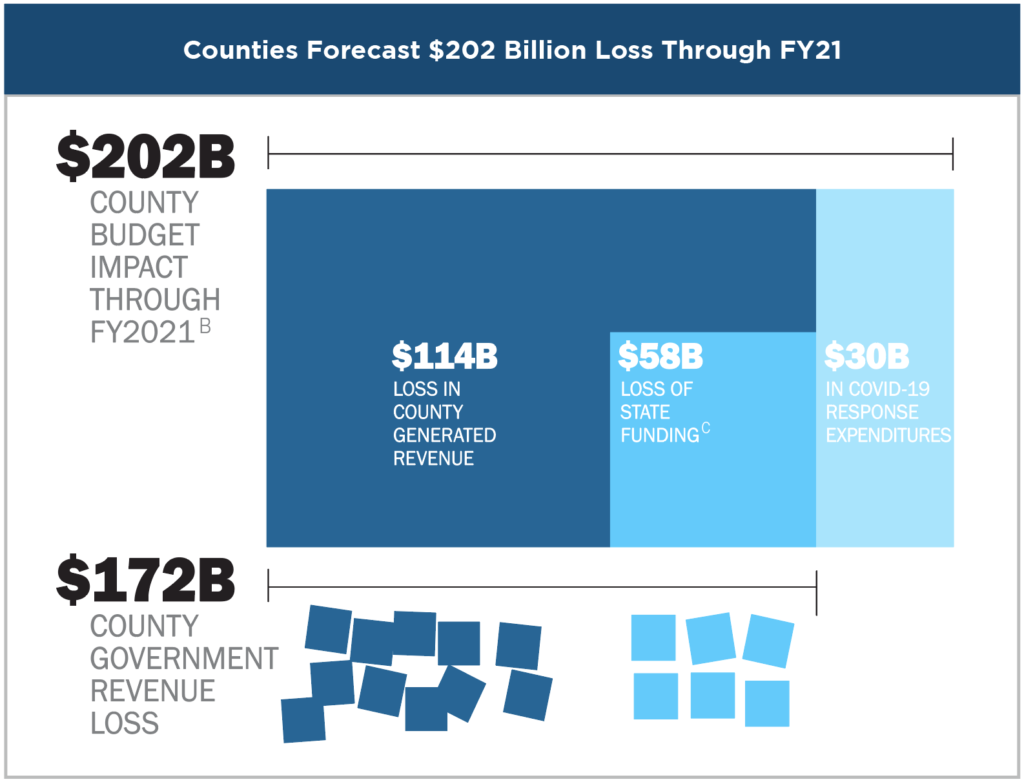

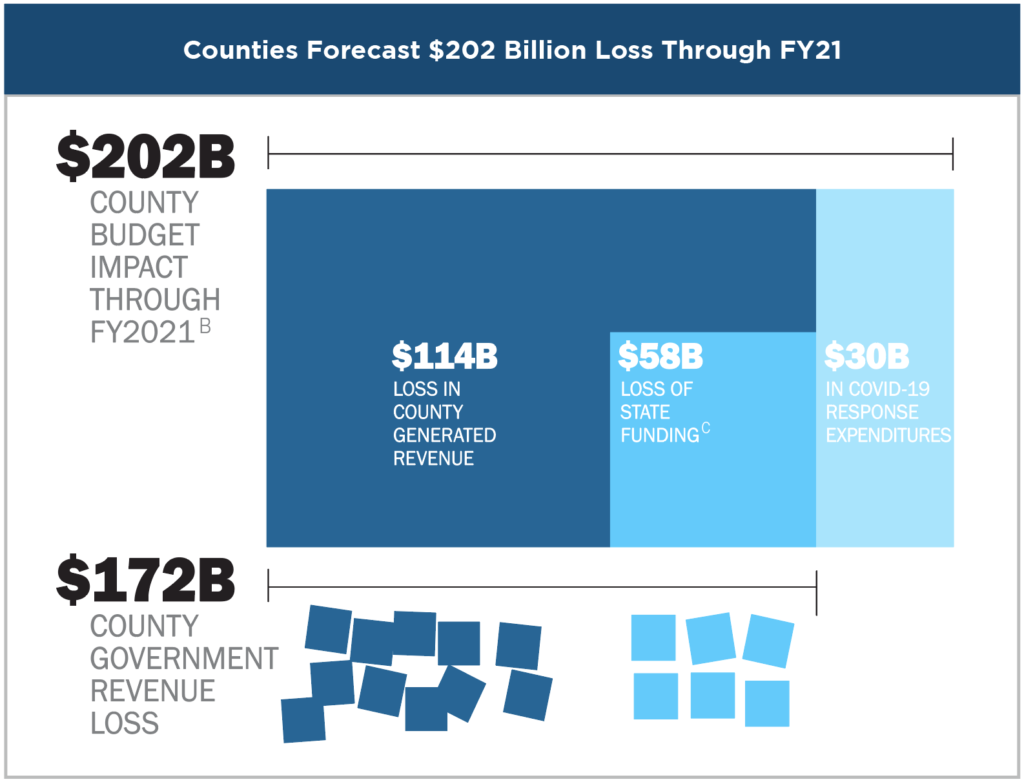

In addition, counties, cities, and towns are experiencing pandemic-related costs that local officials do not expect to be fully covered by CARES Act or other federal funding sources. NACO forecasts a negative $202 billion impact to county budgets through FY2021. As shown in Chart I, this is comprised of $30 billion of additional expenditures due to the pandemic, $114 billion of lost county-generated revenue, and a $58 billion cut in state funding for counties.

Chart I. Source: NACO.

On average, cities anticipate a 13% decline in FY21 general fund revenues versus FY20, according to the August National League of Cities (NLC) report City Fiscal Conditions 2020. NLC notes that most municipalities’ FY20 budgets were in effect for only a portion of the pandemic recession, and therefore FY20 more closely represents a pre-recession baseline of city fiscal conditions. NLC analysis indicates that a one percentage point increase in unemployment results in a 3.02% budget shortfall for them. NLC’s conclusion is that cities and towns will experience “over $360 billion in lost revenues between 2020 and 2022, with shortfalls nearing $135 billion in this year alone.”

One million state and local government jobs lost in one year

The major state and local associations, or the “Big 7,” include the National Governors Association, NACO, and NLC. The groups have consistently advocated for $500 billion in unrestrained federal aid to states and localities to offset pandemic-caused revenue losses. States and localities collectively employing 13% of the U.S. workforce laid off or furloughed 1.5 million workers in the spring. There has been some job recovery, but in a joint statement, the Big 7 forecast that the job loss will continue: “A third of cities already have begun to furlough or lay off essential municipal workers while nearly half are planning to institute hiring freezes. A quarter of counties have also had to reduce their workforces.” The nearly 3 million city and municipal jobs are impactful in small towns—small municipalities (fewer than 50,000 residents) account for more than one-third of the jobs, while big cities (over 500,000) fall closely behind.

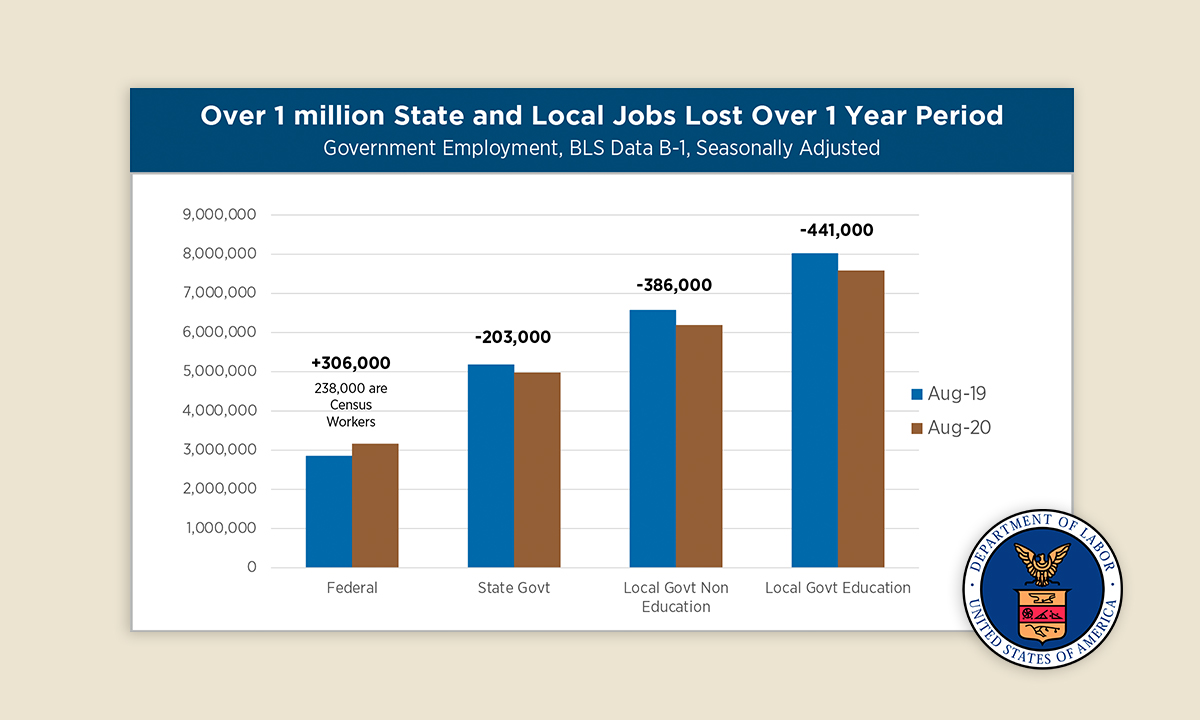

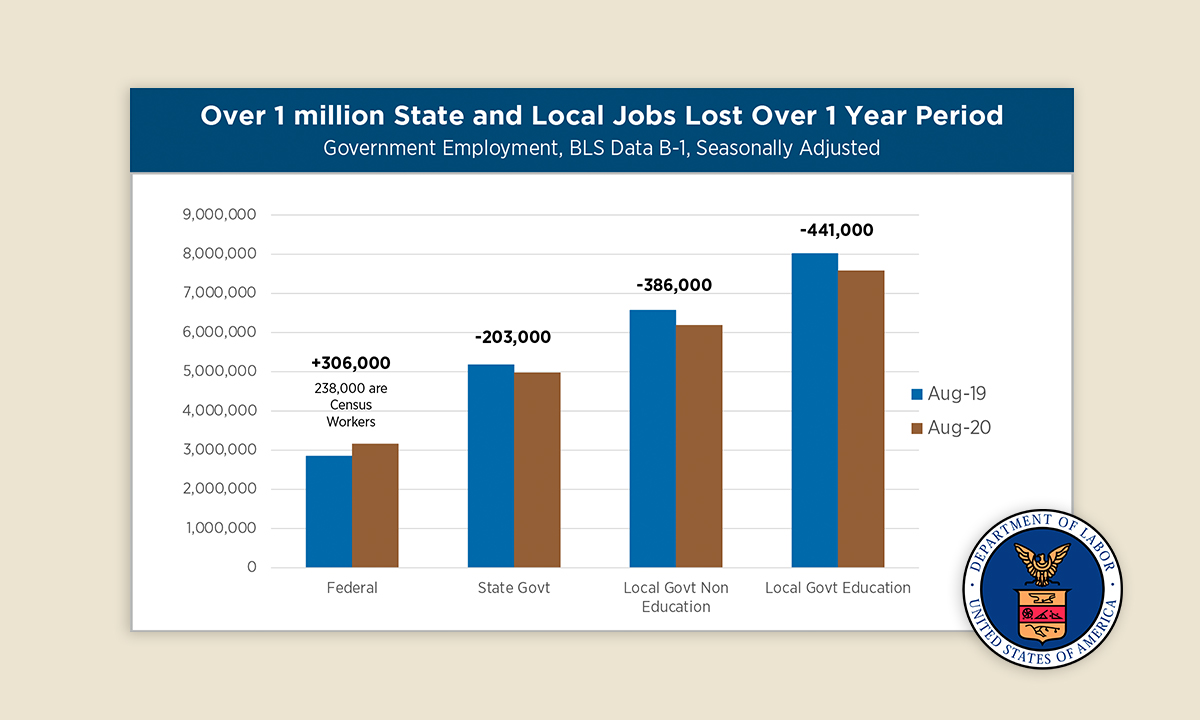

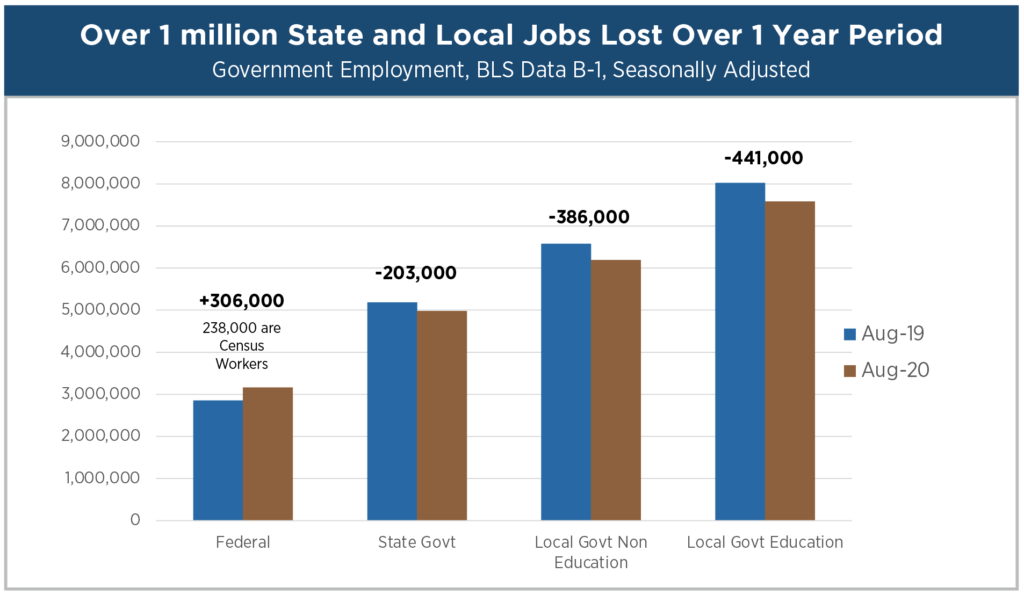

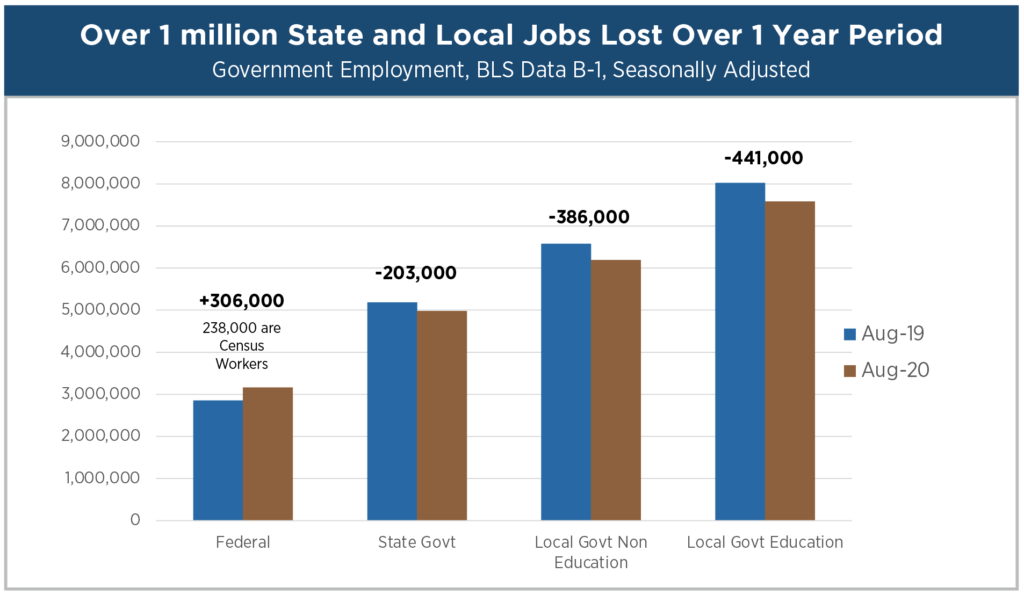

The latest Bureau of Labor Statistics data (September 4th) support the claims of the states, counties, and cities. Data indicate that State employment dropped slightly (2,000 jobs) from July to August, while local government gained 95,000 jobs. However, in a year-to-year comparison, from August 2019 to August 2020 (see Chart II), state and local governments have lost more than one million jobs—state government is down 203,000 jobs and local government employment declined by 826,000.

Chart II. Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, FBIQ.

Eliminating jobs is a last resort for local officials, especially in an election year. Most localities have delayed those decisions until all other possibilities are exhausted. Mayors and Governors have cut or delayed initiatives, projects, services and capital improvements. They have used rainy day funds and one-time trust funds to the extent available. Furloughs, pay cuts, and eliminating vacant positions have also been part of the mix. California’s FY21 budget includes $11 billion in specified “trigger” spending cuts that take effect (and cause significant layoffs) unless the state receives $14 billion in federal aid by October 15th .

An example from Onondaga County, New York, shows the trade-offs and challenges of the upcoming tough decisions: Onondaga County faces an $80 million deficit AFTER making significant cuts, including cancelled contracts, early retirements, reduced hours for employees, and eliminated positions. The County also implemented a new energy tax and used $15 million in reserves. On September 1st, County Executive McMahon was given authority to lay off 250 workers. Before taking that step, he is waiting to see whether sales tax revenues improve or if the federal government passes an aid package. Cutting 250 jobs, plus the 160 retirements, is a 14% reduction to the county’s 3,000-person workforce (1,200 fewer than before the Great Recession). The largest portion of the workforce is the Sheriff’s office, followed by social services, water/utilities services, and the health department.

Some counties, such as California’s Los Angeles County, adopted a budget at the start of their fiscal year (July 1st) but delayed layoffs until the fall. Facing a $953 million shortfall, the county adopted a revised budget that includes 8% reductions to all departments, elimination of 3,251 positions, and 655 layoffs starting no earlier than October 1st. Like many counties, law enforcement represents the largest portion of the budget and is subject to the largest overall reduction: a cut of $145 million and up to 346 layoffs. The county accessed $352 million in one-time trust account reserves to reduce personnel and program cuts.

The failure of Congress to reach a compromise on a new coronavirus relief package imperils the ability of state and local government to maintain sound operations and critical services for residents, and puts jobs further at risk for the 15 million public servants carrying out services on the ground ranging from health care to education to public safety.

Joint statement by Big 7 state and local government organizations,

August 13th

What’s Next?

As Congress and the Administration fought through August and into September, the state and local associations voiced their collective concerns (see quote above).

The upcoming election is not just about Washington, D.C. Most of the governors, mayors, county executives, and local officials making tough budget calls—and potentially cutting jobs of their own constituents—are also on the ballot in November.

UPDATE

On October 1st, the House passed a $2.2 trillion Heroes Act with a partisan vote of 214-207. That legislation includes $436 billion in state and local funding. Treasury Secretary Mnuchin is negotiating on behalf of the Administration and reportedly is working with an overall total of $1.5-1.6 trillion, which includes $250 billion in state and local aid. Regarding the stimulus package, President Trump tweeted on Saturday from Walter Reed Medical Center, “WORK TOGETHER AND GET IT DONE.”