State spending continues to be robust, even as the height of federal COVID-funding in FY21 and FY22 trail off. States rely on a mix of federal funds, general state funds, special purpose state funds, and bonds. General funds are their largest funding pot (except in FY21 and FY22), historically accounting for about 38% of the total budget. The general fund accounts are growing with the economy; many states are enjoying budget surpluses. Evidence of the surpluses is shown in the healthy condition of state budget stabilization accounts (or “Rainy Day” funds). Overall, according to the FY23 Fiscal Survey of States done by the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO), state Rainy Day funds cumulatively total over $157 billion, which equates to 13.8% of median state expenditures, as compared to 7.9% in FY19 and just 4.4% five years prior.

While Rainy Day fund balances and policies vary widely by state, the continued growth of budget backstop accounts indicates healthy state budgets and bodes well for smoothing the decline of federal COVID funding. Revenue growth for FY24 is expected to slow; however, NASBO projects that state general fund budgets for fiscal 2024 will total $1.26 trillion. That represents a 6.5% increase in spending over FY23. All but four states exceeded FY23 revenue projections reported to NASBO, helping solidify the rosy projection. The positive financial picture for most states means that they will start spending down some of their balances, likely through a combination of tax decreases, enhanced public services (including filling in COVID funding gaps), and investments.

WINDOW INTO STATE AND TERRITORIES USES OF SLFRF

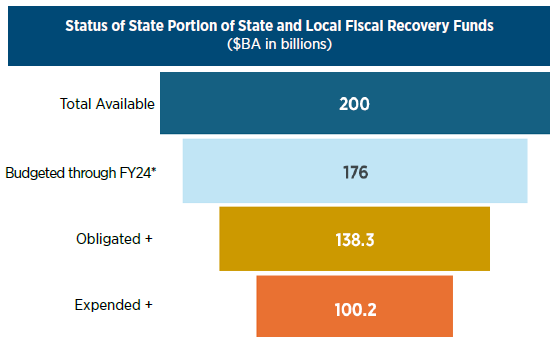

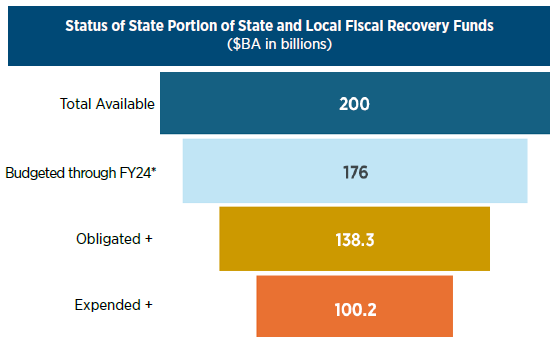

States and Territories are budgeting for, obligating, and spending their $200 billion from the State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund (SLFRF), created by the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA). As shown in Chart I, they have cumulatively budgeted for 88% ($176 billion) of the total funds available, as of September 30. As FBIQ projected, obligations and expenditures have lagged behind budgeting.

Chart I. Sources: Dept of Treasury 6/30/2023 and 9/30/2023 reporting; NASBO 10/19/2023 budget blog. *Reported 1/16/2024 based on 9/30/2023 data. +Reported 10/2023 based on 6/30/2023 data.

ESSENTIAL 2024 FUNDING DEADLINES

Critical deadlines for SLFRF come at the end of calendar 2024. All SLFRF funds must be obligated by December 31, 2024, and expended by December 31, 2026. Some funds, such as for Surface Transportation projects, have an earlier obligation deadline of September 30, 2024. The Department of Treasury has issued a series of rules about use of the funds. The latest Interim Final Rule was published November 20, and addresses specific questions about the December 31 deadline for sub-recipients and contractors, as well as the ability of the original recipient to de-obligate and reuse funds after December 31. Per the rule, if the original recipient of the federal funds enters into an agreement with a sub-recipient or contractor by December 31, the deadline requirement is met. The subaward recipient does not have to obligate or contract for those funds by December 31, 2024.

STATE DETAILS AND FUNDS FOR LOCALITIES

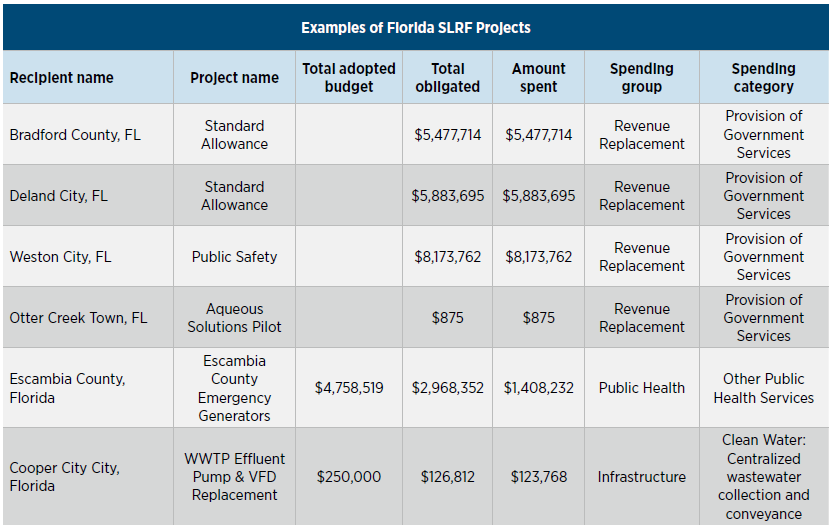

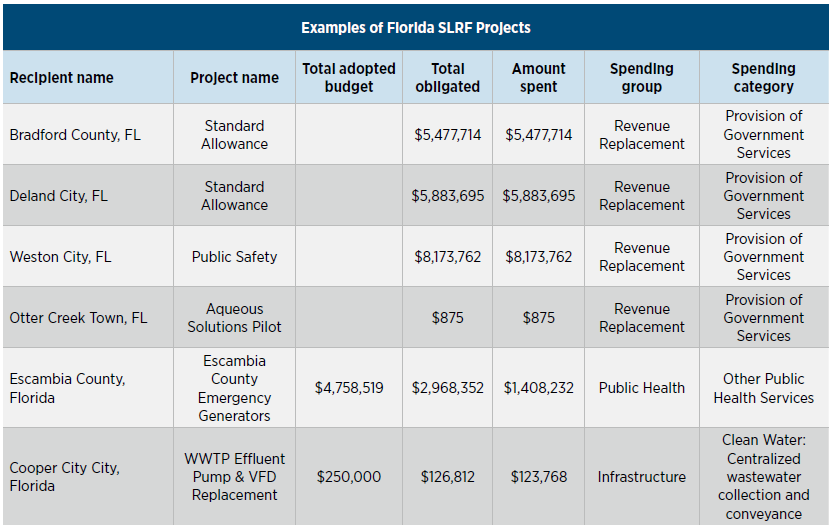

With a deadline looming, and each state facing a complex mix of priorities and projects, looking at states that have more funds left on the table is useful. States range in their percentage of budgeted, obligated, and expended SLFRF funds. States that have budgeted less than 60% of their allocations include West Virginia, Nevada, Alabama, Louisiana, Georgia, and Arizona. Other opportunities may come from Tribal and local government SLFRF funds. SLFRF provided a combined total of $150 billion in funds to: Tribal governments ($20 billion); Counties ($65.1 billion); Cities ($45.6 billion); and smaller towns or government units ($19.5 billion). Those expenditures are tracked separately, and smaller localities are only required to report annually. Details on Tribe projects are collected but not posted by Treasury. To look at state-by-state or even town-by-town SLFRF projects, pandemicoversight.gov offers many map-based interactive tools. An example is Florida’s project and summary information shown in Chart II.

Chart II: Pandemic Oversight Data. Source: Pandemicoversight.gov

States are spending the flexible SLFRF funds on a wide variety of programs and priorities. The categories of spending are so broad that projects can fit in multiple categories; therefore, data isn’t consistent, either from state to state or over time. As states and localities were implementing SLFRF, they had challenges (including COVID, outdated IT, and staffing issues) and asked for the Department of Treasury’s help to properly administer the funds, including clarification of rules and reduced reporting requirements. Treasury worked to reduce reporting burdens, making it easier for states and localities but more challenging for organizations and companies tracking spending. The latest report is Treasury’s January blog post, which highlights selected projects and provides an updated summary of key SLFRF investments.

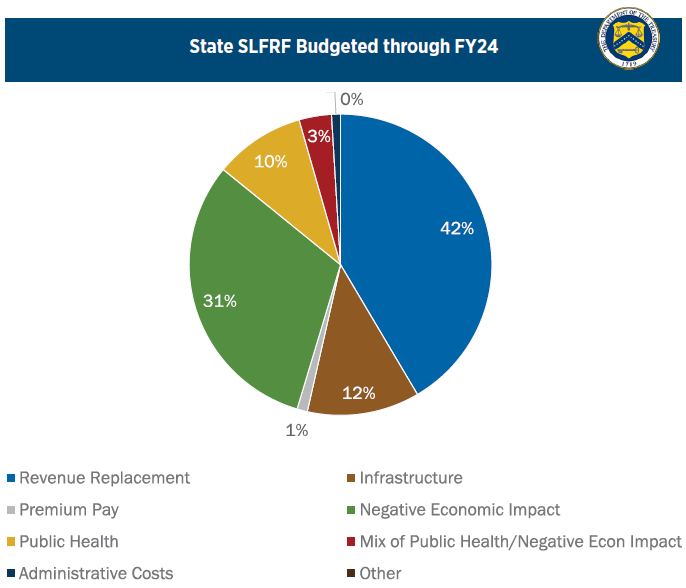

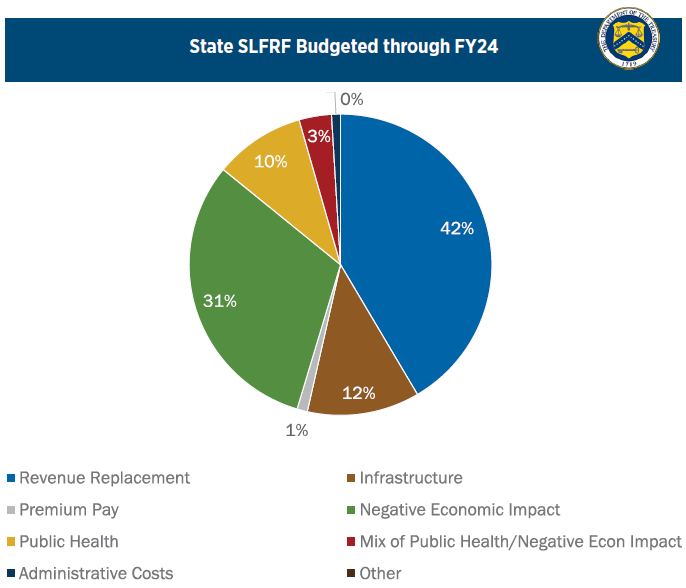

Overall, as illustrated in Chart III, states have primarily used SLFRF to deal with revenue loss (42% of the total budgeted); second to deal with economic impact of the pandemic (31%), and third on public health needs and related negative economic impact (13% of total budgeted funding). Many states placed revenue loss funds into their general fund to provide maximum flexibility as the pandemic unfolded. They can legally use those funds for a multitude of purposes. Another tracking challenge is that even specified projects, such as those for “necessary investments in water, sewer, or broadband infrastructure” may be counted in either the revenue loss category or as infrastructure investment. States took different reporting approaches, making comparisons of spending priorities difficult.

Chart III. Source: US Treasury, data as of 9/30/2023

INSIGHTS FROM GOVERNORS: “LACK OF MODERNIZED DATA SYSTEMS HAMSTRUNG STATES”

Oversight and analysis of SLFRF funds is ongoing and benefits from different perspectives. On January 10, the National Governors Association (NGA) published their first major “after-action” analysis focused on pandemic fund use, focused on COVID child care and early childhood funding, titled “Optimizing Federal COVID Relief Funds: State Perspectives On Bolstering Child Care And Early Childhood Systems.” NGA identified five key factors and analyzed extensive data from 14 states. The report looks at how 1) program priorities aligned with need; 2) state governance structures and coordination; 3) authorizing and 4) disbursing federal funds, including the application process; and 5) modernizing data systems and strengthening data collection.

The lack of modernized data systems and insufficient data capacity hamstrung states in their efforts to address inequities and improve access, especially for populations and locations experiencing the most barriers.

NGA Report,

January 10

NGA identified major challenges that states had due to outdated IT systems, data gaps, and funding staff and vendors to do the work. Many states had IT systems that had not had undergone significant upgrades in two decades. Further, NGA highlighted that “many states initially relied on end-of-life technology or did not have key integrated systems to disburse COVID-19 relief funds, slowing the disbursement process.” Problems arose because of staffing capacity, since state IT staff had many competing and concurrent demands. States also reported challenges in getting vendors and long procurement processes that did not support emergency needs, as well as existing data gaps that hindered decisionmakers.

NGA’s analysis shows that modernizing data systems, and keeping them up-to-date, is critical to the mission of providing government services and being able to evaluate programs. The need for IT data and system preparedness and access to expertise is especially crucial when emergencies arise.

THE 2024 RACE TO OBLIGATE

States and localities are using SLFRF funds to make investments, such as water infrastructure, emergency systems, information technology and education support; to deal with the effects of the pandemic on people, systems, businesses, and nonprofits; and to supplement their general funds in order to make payroll and ensure steady operations. Early on, some states poured funds into their Unemployment Insurance trust funds, but that has not continued as employment rebounded.

The challenge now is time—states and localities must immediately plan for their final SLFRF spending in order to obligate funds by December 31. Smart investments that leave them in the best possible shape post-pandemic are critical. As the National Governors Association report highlighted, investments in updated information systems that enable essential government services will be a critical building block for state and local officials, giving them the information and tools needed to govern responsibly and effectively.