In January, the Department of Defense released, a long anticipated update of DOD Directive 3000.09, Autonomy in Weapon Systems, which establishes “policy and assigns responsibilities for developing and using autonomous and semi-autonomous functions in weapon systems, including armed platforms that are remotely operated or operated by onboard personnel.” Safeguards for use of autonomous weapons include a new review by senior officials prior to the development and deployment of any autonomous weapon systems that do not meet specific exemptions. The 2023 directive replaces the original 2012 directive, acknowledging changes in both technology and the current security posture. Large scale operations in the Middle East and Southeast Asia have been superseded in a new National Security Strategy that requires a pivot, resetting the force for near-peer competition and boosting to autonomous and unmanned programs to address different battlefield challenges.

Every US military service participates in the autonomous, unmanned and robotic arena. Programs include unmanned aircraft, ships, and ground vehicles, robotic mine detectors and forays into other uses for robotics. Changes in technology and mission have made autonomous movement of supplies over challenging terrain an operational priority.

While innovation abounds across the defense department, the Army works to turn requirements into fielded programs through its newest four-star headquarters, Army Futures Command (AFC) in Austin, TX. Work on autonomous, unmanned and robotic equipment takes place within the AFC and its various elements, including Cross Functional Teams, Army Application Laboratory, and the Combat Capabilities Development Command. Much of the funding for these forward-looking requirements is nestled within Army research programs for future systems.

As the largest military service in personnel terms with capabilities in the land and air domains, Army views autonomous systems as force multipliers. Manned/unmanned teaming extended capability for AH-47 Apache aircraft increases lethality. Leader-Follower technology for logistic convoys can save lives with most trucks rolling along without drivers. In the FY24 budget request, the Army seeks program funding for future efforts for vehicles, equipment, and unmanned air systems.

Here are some research and procurement account highlights.

GROUND VEHICLES

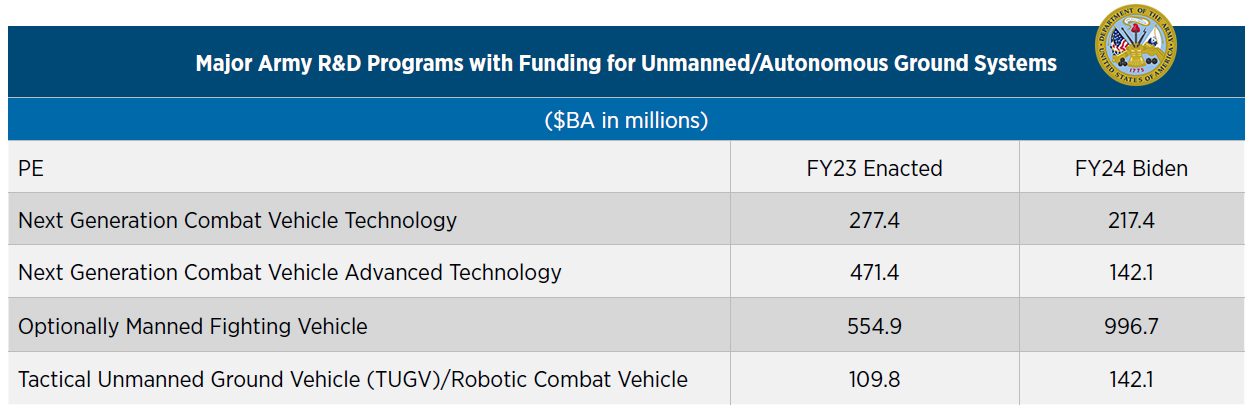

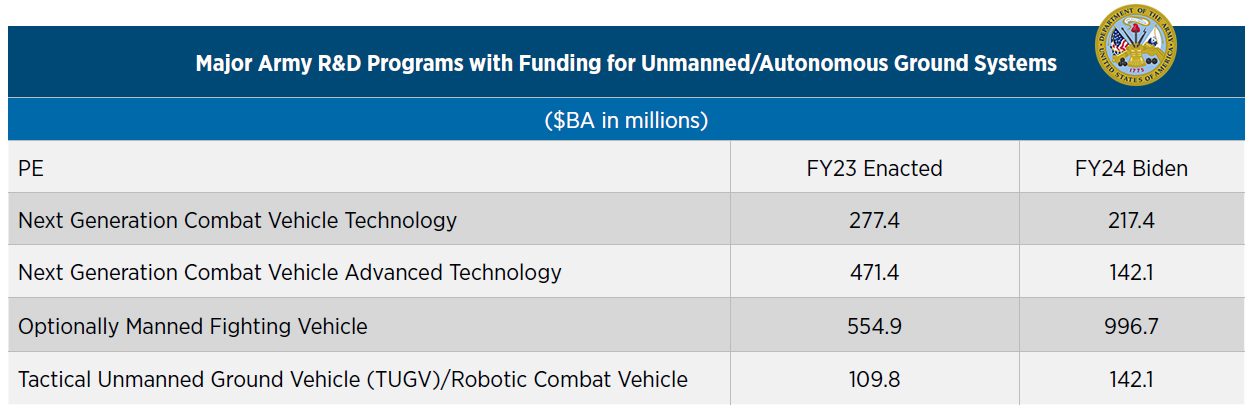

One of the Army’s six modernization priorities is the Next Generation Combat Vehicle. The FY24 request for Next Generation Combat Vehicle Technology is $166.5 million in Research, Development, Testing and Evaluation (RDT&E). The FY23 enacted amount was $277.6 million, of which $103.5 million were Congressional adds. This effort focuses on building upon foundational vehicle architectures to include autonomous architecture. Program elements include Combat Vehicles Robotic Technology, Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Technology, as well as various sensor research for autonomy and protection.

Next Generation Combat Vehicle Advanced Technology is a research program designed to develop and mature promising technologies researched and designed in Next Generation Vehicle Technology. This program, part of an overall effort to potentially replace much of the current fleet of armored vehicles, includes funding for unmanned and autonomous capabilities. The Army requests $217.4 million in RDT&E for FY24 activities. Another Congressional favorite, FY23 funding was $471.4 million, $278.2 million more than the Army’s proposed FY23 spending plan.

In the Army’s quest to replace the current Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicle, Biden’s FY24 budget seeks $997 million in RDT&E for the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV), with $1.7 billion requested over the Future Years Defense Program (FYDP). This latest iteration of the Bradley replacement, previously attempted in the Future Combat System program, Ground Combat Vehicle program and the Next Generation Combat Vehicle, has survived recent starts, cancellations, revisions and restructuring. The vehicle concept is designed to operate both with and without a crew. Currently, FY 2024 funding for OMFV is for OMFV Detailed Design Concepts and material costs for 7 prototypes.

The Army describes the Robotic Combat Vehicle-Light (RCV-L) experimental prototype as “a small, lightweight hybrid-electric unmanned ground combat vehicle that can be transported easily by military aircraft” Under the program umbrella of Tactical Unmanned Ground Vehicle, the FY24 request is $142.1 million in RDT&E, an increase of $32 million from FY23, to produce prototypes. Annual funding across the FYDP is close to the FY 24 amount requested. A new start in FY23, the Army seeks to deliver initial capability by 2030.

Recently, unmanned ground vehicles were the subject of a solicitation on the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) website for an Area of Interest Statement for an autonomous transport vehicle-system seeking commercial solutions to convert existing military vehicles into uncrewed vehicles that can be transported via a Palletized Load System. Funded through an Other Transaction Authority/Agreement, the amount is not stated on the website, however, DIU received $41.9 million for prototyping efforts in FY23 as well as $69.9 million for their organizational activities. The FY24 request is $104.7 million, a substantial increase from their FY23 $42.9 million request.

Chart I. Source: FY24 Army Budget Justification Materials.

AIRCRAFT

The Army has a new start in FY24 within the Future UAS (FUAS) Family, requesting $53 million in procurement to purchase four Future Tactical Unmanned Aircraft Systems (FTUAS). Over the FYDP, funding and quantities increase, with increases of 130 systems from FY24 to FY25 and 193 systems from FY25 to FY26. Funding also increases in FY25 with $153.4 million and $248.4 million in FY26. The program may have to wait until Congress passes a final FY24 Defense Appropriation Act to begin work on this new start, unless a continuing resolution anomaly for this program is granted.

The Army Requirements Oversight Council approved the FUAS Initial Capabilities Document in March, 2019, including requirements for Future Tactical UAS (FTUAS), Air Launched Effects (ALE), and Scalable Control Interface (SCI). The FTUAS may replace the RQ-7Bv2 Shadow, used by Army units to increase situational awareness and high-value target tracking.

According to the Army, “Manned, optionally-manned, and unmanned systems will penetrate defense-in-depth environments by employing ALE [Air Launched Effects] with teaming and swarming effects to detect, decoy, jam radar and communications, conduct cyberattack, spoof and jam Global Positioning System (GPS), and kinetic engagement.”

Another unmanned aircraft program with a big planned FY24 increase is the Small Unmanned Aircraft System. The procurement program bought 207 Short Range Reconnaissance (SRR) Systems in FY23 for $11 million. In FY24, $21 million is requested for 459 SRR systems consisting of 2 air vehicles, 1 Handheld Ground Control Station (HGCS), Digital Data Link (DDL) and Electro-Optical/Infrared (EO/IR) Payload.

The Army’s long-standing workhorse UAV, the MQ-1C Gray Eagle Extended Range, Multi-Purpose Unmanned Aircraft System received a $350 million Congressional Add for 12 UAVs for the National Guard in FY23. The Army did not request Gray Eagles in FY23 or FY24. In FY23, Congress added $120 million to the Army’s $13 million Gray Eagle Mods2 request for extended range multi-domain operations. The FY24 request for Gray Eagle Mods2 is $14.9 million, to modernize communications by adding Link 16, a tactical data link network used by NATO members. The MQ-1 payload FY24 request is $13.7 million, down from $72.7 million enacted in FY23 ($15 million more than the Army requested).

Sprinkled throughout the Army’s FY24 budget is funding for robotics, unmanned and autonomous efforts. Lessons from the twenty years of the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and fighting ISIS advanced unmanned aircraft for surveillance and lethality. A near-peer conflict means a less permissive environment in terms of freedom of movement in any domain (especially air), requiring more survivable systems and more unmanned systems. Increased survivability and effectiveness against more sophisticated adversaries require increased cybersecurity, stealth, and autonomy. The FY23 Defense Appropriations Act was generous to autonomous and unmanned efforts with few decreases to amounts requested and, in several cases, millions in Congressional increases. To increase capabilities for the Indo-Pacific theater, the Army has staked a position in autonomous and unmanned vehicles and aircraft in its FY24 budget.

WHAT’S NEXT?

Expect enemies in future conflicts to employ more technology than the enemies faced in the past two wars. Electronic warfare and cyber threats to communications between controllers and unmanned systems, threats to GPS, sophisticated air defense systems and sensor arrays will require greater capabilities for unmanned systems. A big part of meeting that challenge is increased autonomy which will put a premium on artificial intelligence/machine learning. In the coming weeks, the marks made by the Armed Services and Appropriations committees for these programs will signal how much Congress agrees with this evolution in strategy.