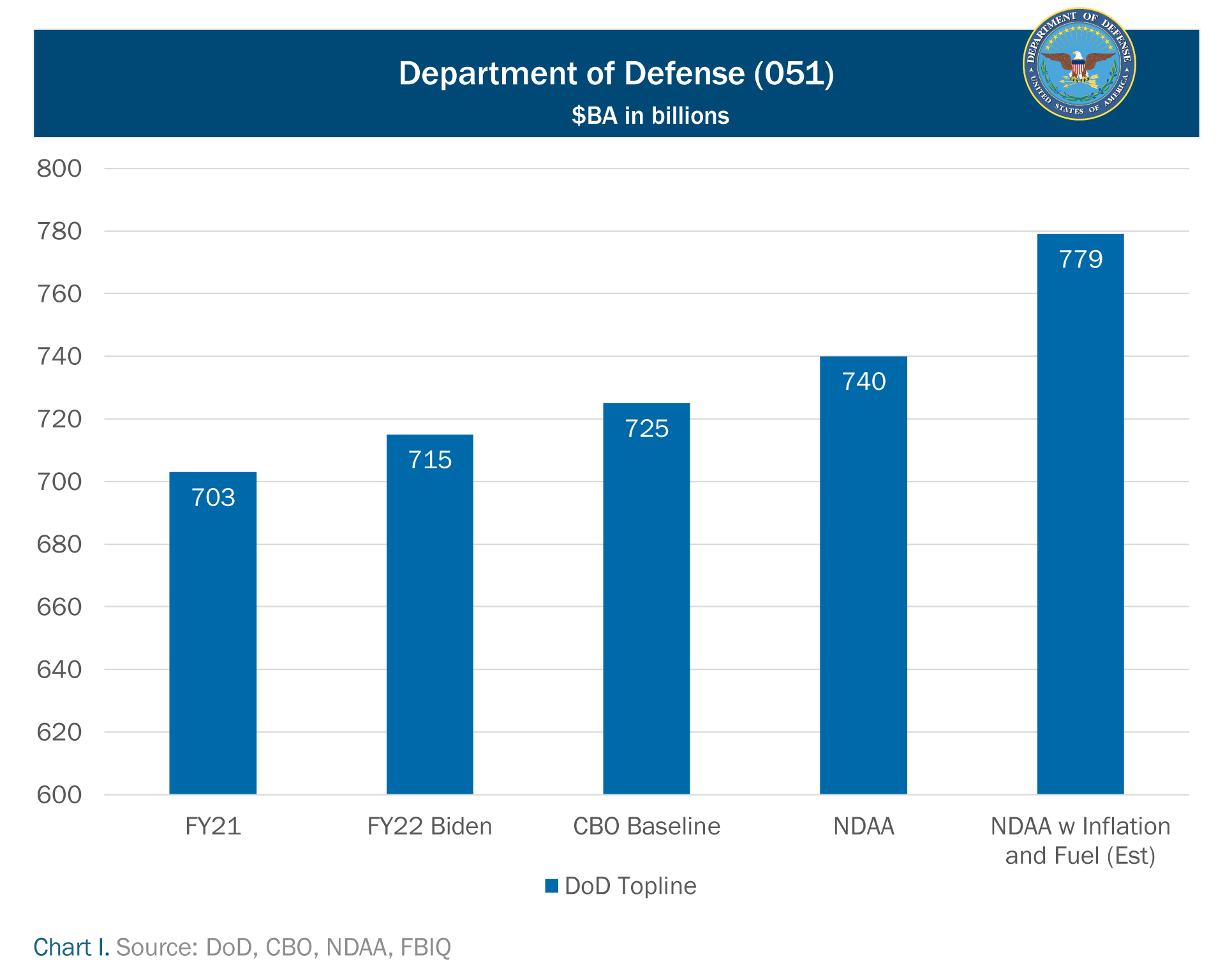

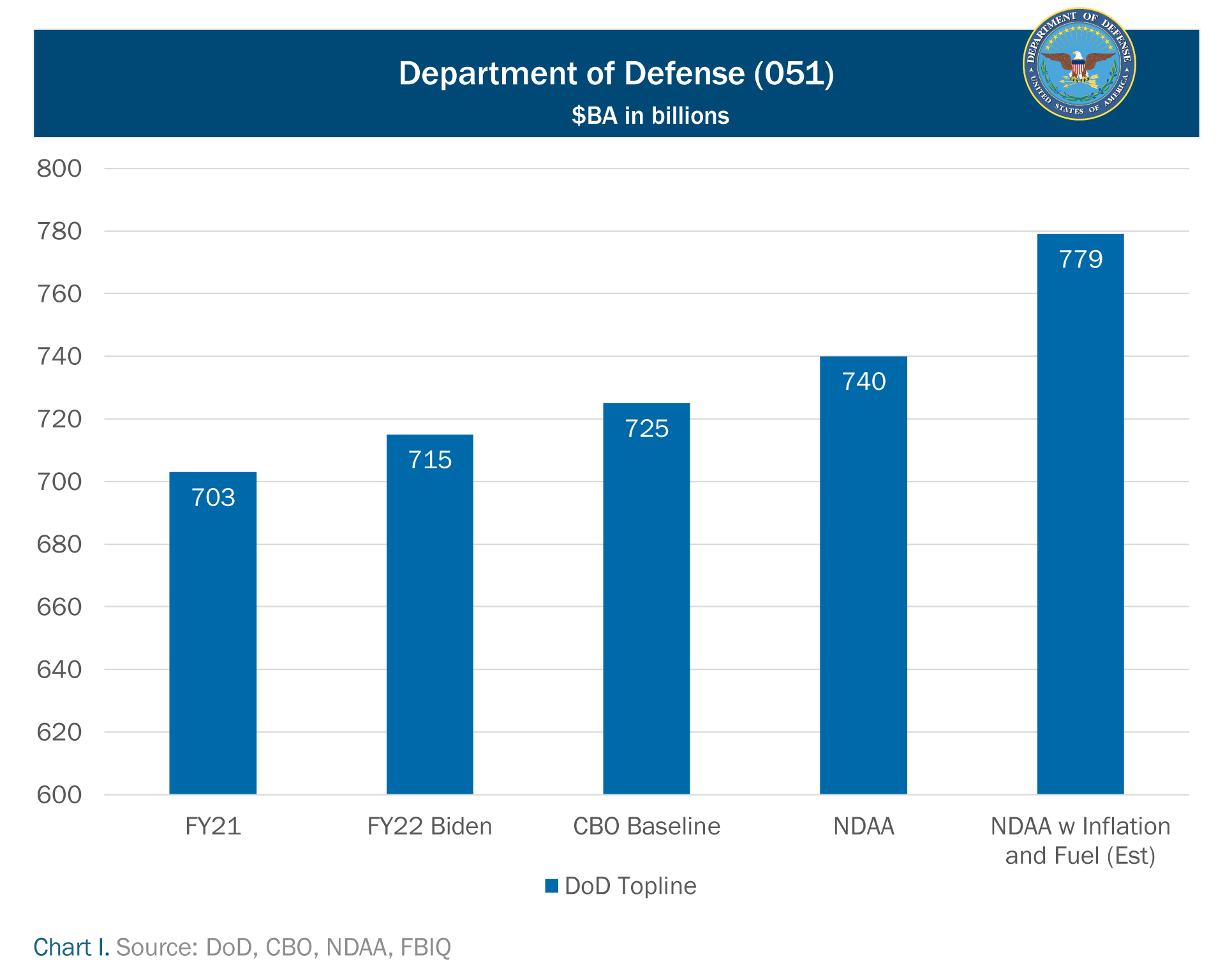

President Biden’s $715 billion FY22 budget for the Department of Defense (DoD) assumed 2.2% inflation and a 10.1% increase in fuel costs. With inflation running closer to 7% and with fuel costs for the world’s largest purchaser of fuel up 30%, DoD faces a $40 billion second half hole in its FY22 budget. For perspective, the FY13 Budget Control Act (BCA) DoD sequester totaled $37.2 billion.

The 2013 sequester set several precedents DoD is likely to follow in FY22 and FY23. For more on DoD’s operational challenges, see Chauncey Goss’s article, “Protracted CR Threatens DoD Initiatives,” on page 5.

LESSONS LEARNED FROM DOD’S 2013 SEQUESTER EXPERIENCE

The 2011 BCA set up a possibility of a sequester (an across-the-board cut to spending) in January 2013 if Congress failed to enact legislation to reduce the deficit. In December 2011, FBIQ predicted that sequestration would be implemented differently than outlined in BCA. As we expected, Congress reduced and delayed its impact.

For a Republican Congress and the Obama Administration, avoiding sequester required that they either: 1) pass a law to eliminate sequestration or 2) reach a bipartisan agreement to increase taxes and cut spending. The first option risked another 10% financial market correction and a U.S. debt downgrade in a fragile economy. By 2013, two attempts by Congress and the Obama Administration to reach a grand bipartisan deficit reduction deal had failed.

In December 2012 and March 2013, Congress passed laws that reduced the FY13 sequester by a total of $29.5 billion and delayed it by two months.

FBIQ argued that DoD, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), and Congress would cooperate to protect agency headcount and minimize the sequester’s impact on key DoD operational priorities. That occurred in three steps. First, Congress passed the FY13 Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act (P.L. 113−6), which expanded DoD’s transfer authority to $11 billion and allowed it to cut $2.5 billion in DoD’s Working Capital Fund balances. Second, in April, OMB signaled to agencies that it would “green-light” reprogramming requests to “reduce operational risks and minimize impacts on the agency’s core mission.” Third, DoD responded with an unprecedented $6.6 billion June 2013 reprogramming request that cut DoD procurement and RDT&E accounts and repurposed Overseas Contingency Operations account savings following the Afghanistan surge to boost DoD’s base operating accounts.

In February 2013, DoD Deputy Secretary Carter estimated that the Defense sequester would trigger 22 furlough days for DoD’s civilian workers. After DoD’s transfers were approved, DoD contract spending dropped 52% in April and DoD’s furlough estimate dropped to 11 days. After the reprogramming request was approved, DoD’s furlough estimate dropped to six days.

FY22 OUTLOOK

DoD now faces a similar set of challenges. It’s unlikely final FY22 funding levels are approved before March, leaving DoD six to seven months to address a budget with $40 billion less purchasing power than planned in the FY22 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). This will force a series of trade-offs like those DoD made in 2013.

Civilian agency planners face more uncertainty with the Senate fate of the House-passed Build Back Better Act (BBB) complicating planning for OMB, civilian agencies, and the House and Senate Appropriations Committees.

For DoD, eliminating the inflation problem requires legislation increasing spending levels above the $740 billion level authorized in the FY22 NDAA (see Chart I). It’s unlikely that most congressional Democrats will support that deal without a similar adjustment for non-defense spending. We expect the vast majority of congressional Republicans to oppose a non- defense spending increase.

The logical alternative, as in 2013, appears to be expanded transfer and reprogramming authorities giving agency managers flexibility to adjust year-end spending priorities, protect headcount, and preserve critical missions. We expect Congress to approve expanded FY22 transfer authorities and reprogramming thresholds. Those changes could be attached to the next continuing resolution (CR).

Agreement on a two-year spending cap deal will be delayed until the Senate determines a path forward on BBB. We don’t expect that to occur before mid-February, requiring approval of another CR for up to eight weeks.

FORECAST

95%: Another FY22 CR is approved before a final FY22 spending deal emerges

A short-term challenge for DoD (and other agencies) is that few outside the Comptroller’s Office have focused on the disruptive operational implications of this purchasing power shortfall. After FY22 funding levels are finalized, expect guidance from the DoD Comptroller and OMB to advise the services to withhold a significant portion of planned procurement and RDT&E spending to increase DoD’s year-end operational flexibility. Following 2013 precedents, expect procurement and RDT&E accounts to bear the brunt of the cuts needed to maintain operational priorities with reduced purchasing power and a compressed and back- loaded FY22 procurement cycle with delays to planned and approved new starts. Together, inflation and billions in transfers and reprogrammings should recalibrate President Biden’s FY23 budget recommendations, DoD’s FY23 operational priorities, and FY23 funding decisions by the House and Senate Appropriations Committees.

FORECAST

90%: Expect a back-loaded FY22 procurement cycle that reduces planned spending levels and delays new starts

The 2013 sequester delayed release of President Obama’s FY14 budget to April 10. We expect a similar delay for release of President Biden’s FY23 budget due primarily to two factors: uncertainty over the fate of President Biden’s Build Back Better initiative (that decision dramatically changes the budget outlook for civilian agencies) and the inflation challenge affecting every federal agency.

FORECAST

80%: Release of the President’s FY23 budget is delayed beyond OMB’s current “early March” schedule.