In July 2022, a memo entitled “A Call to Service to Overcome Recruiting and Retention Challenges” was sent to the Army through traditional command channels as well as shared with the press. Signed by the Army Chief of Staff and Army Secretary, the memo was the basis for a media blitz highlighting the challenging recruiting environment as the reason for the Army’s low recruiting numbers. The memo cites the post-COVID-19 pandemic and current labor market, a low propensity to serve and the lost years of virtual learning restricting recruiter access to high schoolers, and lower Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) scores. The “Call to Service” was not only for personnel currently in the Army but veterans, families and Americans to help fill the ranks.

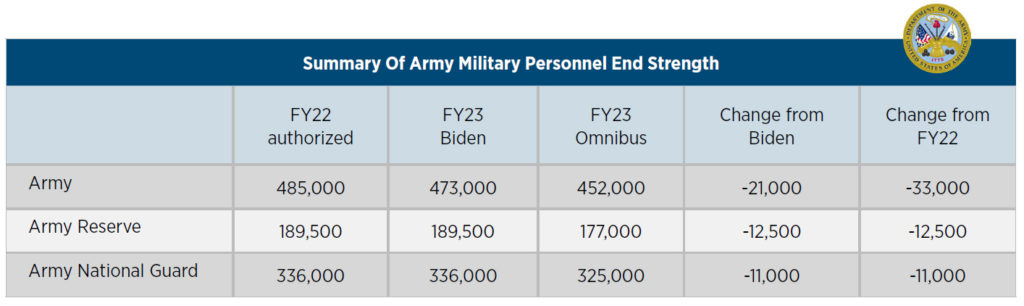

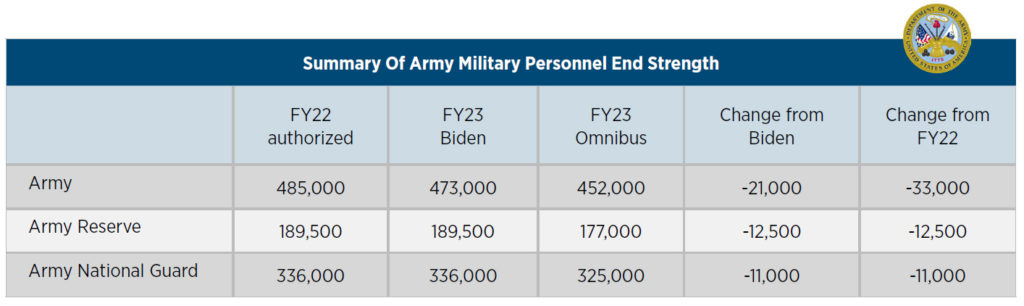

The FY23 Defense appropriations act, Division C of the FY23 Omnibus, reflects the Army’s recruiting shortfalls in a 44,500 reduction in total Army end strength — Active, Guard, and Reserve. Active Army had the biggest reduction of 21,000, with the Army Reserve next at 12,500 and the Army National Guard closely behind at 11,000. The bill also increased benefits, such as subsistence and housing, for all services by about $1.8 billion, about 10% of the total military personnel appropriation. The Army received an additional $609.8 million above the FY23 request across the Active, Guard, and Reserve components for these benefits.

Chart I. Source: FY23 Omnibus Joint Explanatory Statement for Division C

The Army is not the only service to miss FY22 recruiting goals. In a September 2022 Senate Armed Services Personnel Subcommittee hearing on the status of military recruiting and retention efforts across the Department of Defense, the Navy testified the enlisted reserve as well as officer active and reserve goals were not met. The Air Force did not achieve its recruiting goals for either of the Air Force’s reserve components. The Marine Corps credited “an exceptional retention year” as the explanation for how they met FY22 end strength targets. All services are increasing the use of bonuses and overall recruiting efforts to reach the 23% of the 17- to 24-year-old age group qualified to serve. However, the Army finds itself in the direst situation of the three military departments.

In the July 2022 memo, the Army senior leaders acknowledge and define the problem of declining end strength with an admission of the inability to reach FY22 personnel goals as well as FY23 shortfalls. The memo states a projected range of 445,000-452,000 personnel by the end of FY23. The FY23 defense appropriation funds the Army’s end strength at the higher end at 452,000. This gives the Army room to grow in FY23 and decreases prospects for large reprogrammings for assets in military personnel within the year of execution, as took place in FY17 and FY18, or asking Congress to reallocate funds.

While addressing the FY22 recruiting crisis and the range of personnel for FY23, the memo looks forward by discussing the Fiscal Year Defense Program FY24-28 Program Objective Memorandum submission — the request from the military departments and defense agencies to the Office of the Secretary. The assumption for Army end strength was a lower number and while there was no public decision made at the time of the memo to change final force numbers in FY24 or beyond, the option is mentioned. As for the Army’s share of the overall defense budget and how dollars are allocated within the service, the memo makes clear, “The Army fully intends to use any asset gained from a reduced end strength to address critical Army priorities, including modernization to support a smaller, but more lethal force and quality of life improvements to increase retention and satisfaction in serving.”

With the continuing expansion and dependence on artificial intelligence, unmanned aircraft and vehicles, and robotics, there will be “less boots on the ground” and more “seats in chairs” as the nature of warfare evolves. Military personnel accounts for almost 25% of total defense funding within the defense appropriations bill. A small decrease in personnel creates budget flexibility, facilitating budget deliberations and funding increases for other priorities.

The Army received an additional $609.8 million for all three components at the same time as end strength was reduced.

The increase reflects the increased costs per service member, including higher pay. That hints at another part of the story. Shifting to a smaller, more technologically capable force designed to address threats from potential adversaries working diligently on long- range battlefield missiles, cyber and electronic warfare capabilities and artificial intelligence has strategic, operational, and budgetary implications. Former Deputy Defense Secretary Work advocated that objective during the Obama administration. Getting there requires a more capital-intensive approach. This approach isn’t without near-term risk; deterrence requires sufficient end-strength as well as a technological edge vis a vis a potential adversary such as China that can put large forces in the field.

Secretary Austin’s FY23 Budget called for the largest increase in DOD “investment” spending —RDT&E plus procurement. The fact that Congress approved an even larger increase in FY23 signals that shift is underway.