The complexity of planning and budgeting in a major recession caused by a pandemic is daunting. States face uncertain projections fueled by a myriad of unknowns about COVID-19’s spread, persistence, and vaccine and treatment options, but for states it still comes down to numbers.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), early estimates of state revenue losses are upwards of 15% to 20% and increasing. At least 12 states have authorized the use of reserve funds to address lost revenues. States and localities are also laying off and furloughing employees, creating second-order financial challenges, particularly in states with a large share of state government workers as a percentage of overall employment. For example, AK is highest at 25%, and substantial percentages of state employees exist in swing states such as VA (20%), GA (14%), CO (13%), WI and OH (12%), and PA (10%).

As National Association of Counties (NACo) Executive Director Matthew Chase wrote to the House Budget Committee on June 3rd, “Nationwide, the results are seen in the latest [April 2020] jobs report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), which shows a loss of more than 800,000 jobs in the local government sector, 332,000 of which were non-education related jobs ranging from law enforcement officers to health care practitioners, social workers, maintenance crews, construction workers, administrative support and more. These workers are vital to the nation’s COVID-19 response and recovery.”

Personal income and sales taxes comprise the bulk of state revenues. These sources diminished significantly since April and are not projected to pick up until the U.S. economy recovers. According to NASBO, about 75% of the non-federal state revenues are from personal income tax (44%) and sales tax (30%). Transportation-related revenues, such as tolls and fares, have also fallen dramatically.

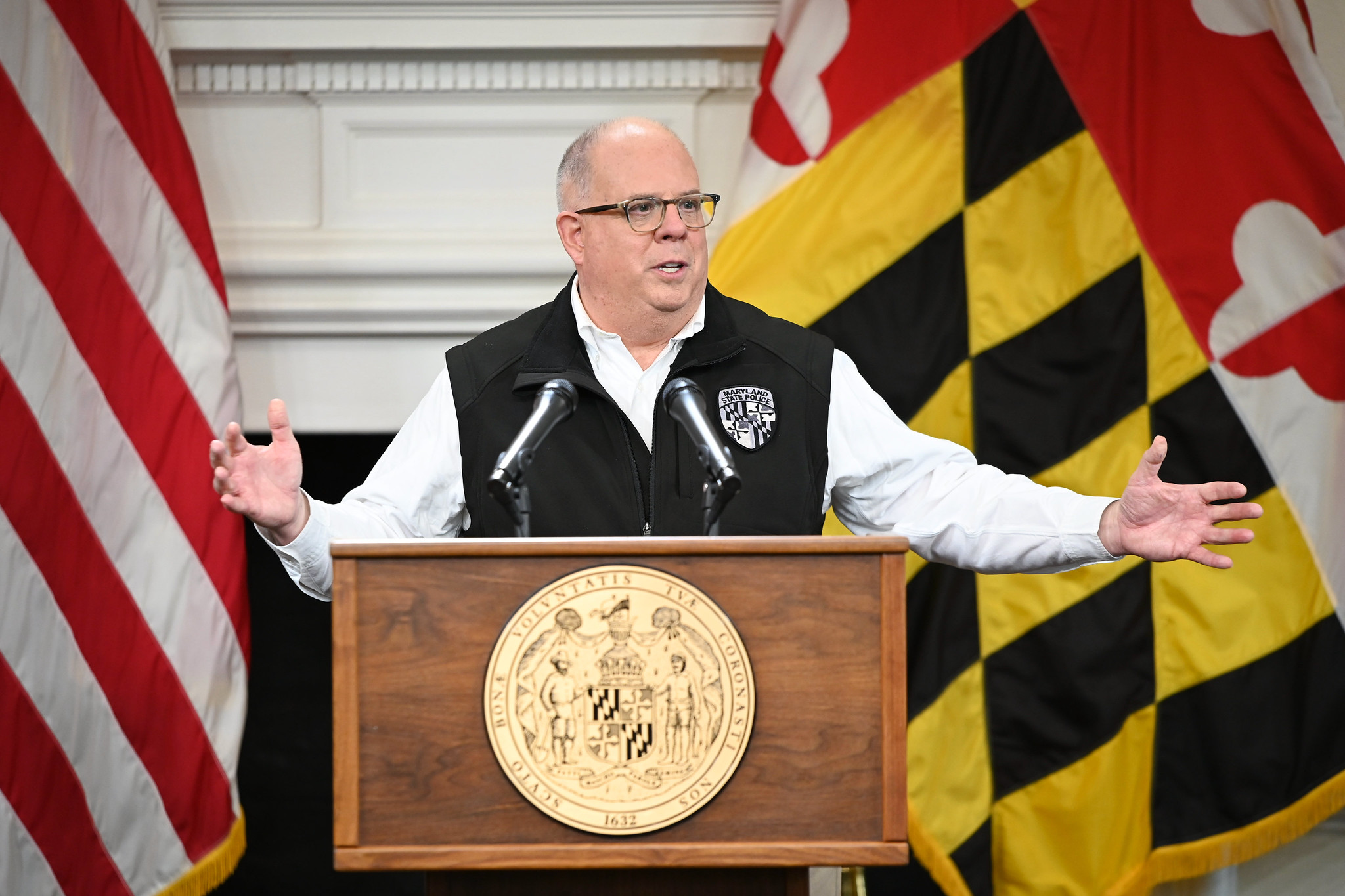

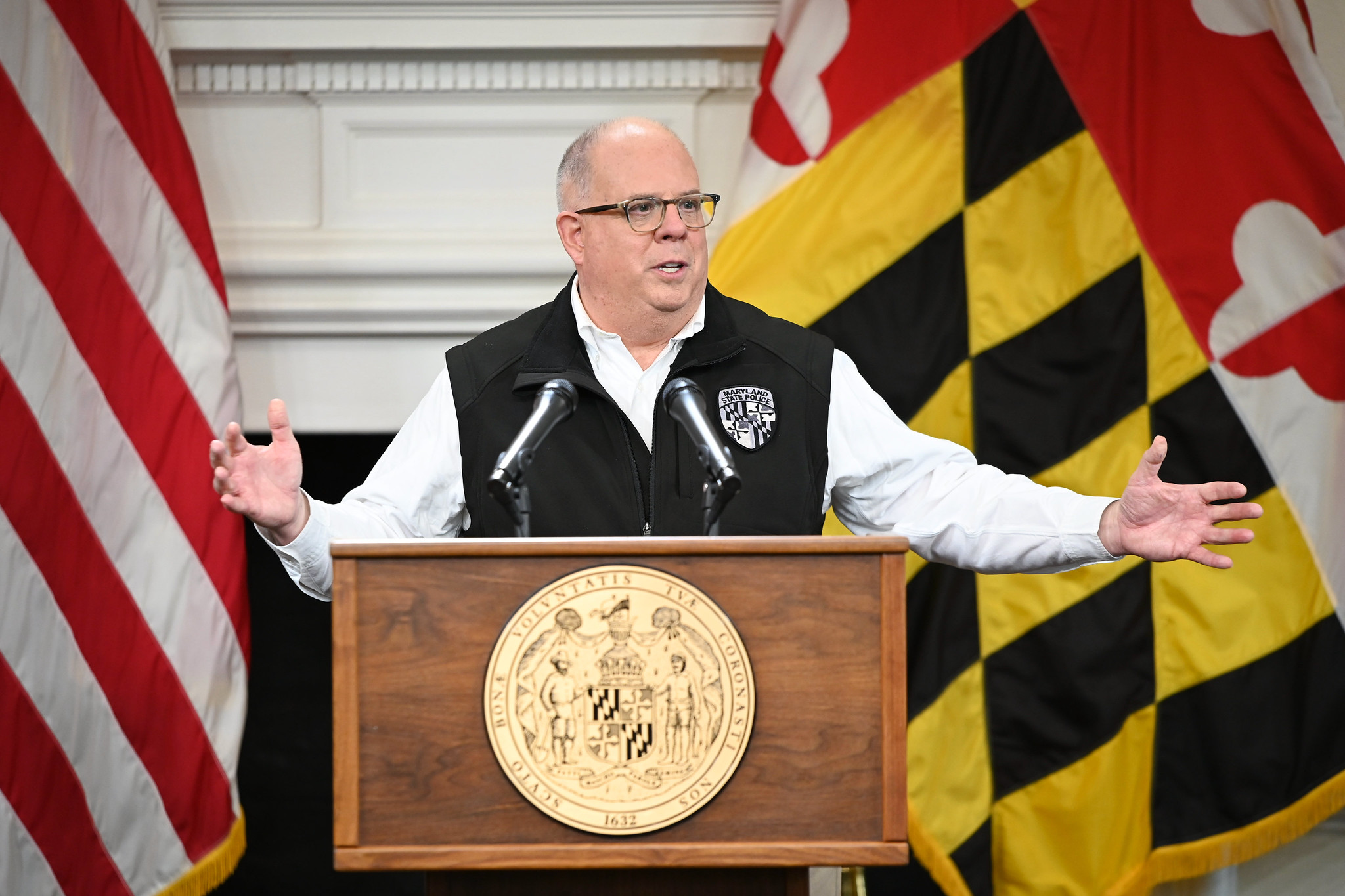

This is the worst ‘State of the States’ budget I have seen… much worse than the Great Recession. This [downturn] has been quicker and more deep. For example, Maryland saw half a million unemployment claims in 8 weeks—in the last recession, it took 72 weeks to get to that level.

National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO) President Nicole in “Coronavirus Cripples State Budgets”, WBUR interview June 12th

“Balancing Strategy”

How can states meet statutory balanced budget requirements (in effect for 49 states) without overcorrecting? Options include:

- “Turn off” as much as possible to reduce expenses: cancel initiatives, including technology buys and new hires, make across-the-board cuts, defer obligations and postpone capital projects.

- Conduct furloughs and lay-offs.

- Pursue CARES Act reimbursements for eligible COVID-19 costs.

- Use state rainy day funds.

- Federal government funding to fill revenue gaps.

- If needed for liquidity, tap loans/municipal bonds.

The Three Backstops: State Rainy Day Funds, Federal funding, and Borrowing

State rainy day funds were getting headlines in December 2019 for all the right reasons-—such as “States Stung by Last Recession Build Record Savings for Next One” (Bloomberg). At the beginning of 2020, states, on average, had reserve funds of 10% of general fund spending. The 7.8% median is up from 1.6% in 2010. While the rainy day fund balances aren’t enough to make up the full revenue losses, they buy states time before austerity measures are required.

Both timing and politics are key factors in obtaining additional federal aid, with liquidity issues playing a major role. Most local governments and 45 states’ fiscal years begin July 1st. Governors and localities have made compelling arguments for the need for unrestricted federal aid to combat revenue losses. The House-passed Heroes Act included $915 billion in funding for states and localities; six Senators introduced the SMART Act on May 18th to establish a $500 billion Coronavirus local community stabilization fund. The Senate has taken no action on either bill.

As states and localities wait for Federal action, those lacking adequate reserves need capital to manage through the disruptions to their revenue streams. Many governors, county councils, and mayors have already announced cost-savings measures, including layoffs.

Public capital markets routinely help sub-federal units of government smooth funding pressures through the fiscal year funding cycle. In the first quarter of this year, liquidity concerns in the repurchase market were followed in real time by coronavirus lockdown mandates. The combination spiked municipal bond market credit prices.

The Fed’s Municipal Liquidity Facility

The Federal Reserve Systems responded to financing disruptions first by buying assets from the banks and other financial institutions responsible for repo market operations and then by introducing unprecedented support for public sector bond markets. While all ten lending facilities opened or renewed by the Fed board helped squeeze pricing dysfunction out of markets, the Federal Reserve also has, through the CARES Act, been authorized to set up the Municipal Liquidity Facility (MLF), which can purchase up to $500 billion of short-term notes from states, local governments, and some governmental enterprises in order to ensure availability of liquidity during the emergency.

The board created the MLF on April 8th and revised its terms to expand the list of eligible borrowers on April 27th and June 3rd. To date only Illinois has tapped the facility. New Jersey may be next as the state legislature debates a borrowing measure. Psychological effect is one durable aspect of Fed announcements (so-called “forward guidance”); this phenomenon worked again as muni financing market pricing returned to pre-virus levels shortly after creation of the MLF. From a large publicly-traded financial institution’s muni banking group, we understand that contacts with state/local issuers were non-existent from mid-March until a few weeks ago. The MLF hasn’t and won’t fix revenue problems, but it has signaled to issuers that funding markets will be supported.

Through its actions, the Fed is alerting Congress that fiscal rather than monetary policy is the more enduring form of assistance to revenue-challenged state and local governments.

State Contraction Can Undo Federal Expansion

It is not lost on Congress or the Administration that the financial position of states is crucial to the country as a whole. As Moody’s chief economist Mark Zandi pointed out June 1st in Politico, “There wasn’t a lot of evidence that state aid would be good stimulus in 2009, but now there’s a lot of data, and it all adds up to juice for the economy… If states don’t get the support they need soon, they’ll eliminate millions of jobs and cut spending at the worst possible time.”

Fed Chairman Powell furthered that concern in his June 16th testimony accompanying the Semiannual Monetary Policy Report to the Congress. After highlighting the MLF’s role in supporting states and municipalities, he noted that “direct help to people, businesses, and communities… can make a critical difference not just in helping families and businesses in a time of need, but also in limiting long-lasting damage to our economy.”

Economics and politics will meld. Taken together, concern about state contraction, state and local liquidity, social pressures and widening economic inequities, and an upcoming national election all point to additional, substantial Federal assistance this summer. The size of and restrictions on the funding will be intensely debated, but with a new school year rapidly approaching, no candidate on a November ballot wants to take responsibility for large-scale teacher layoffs.